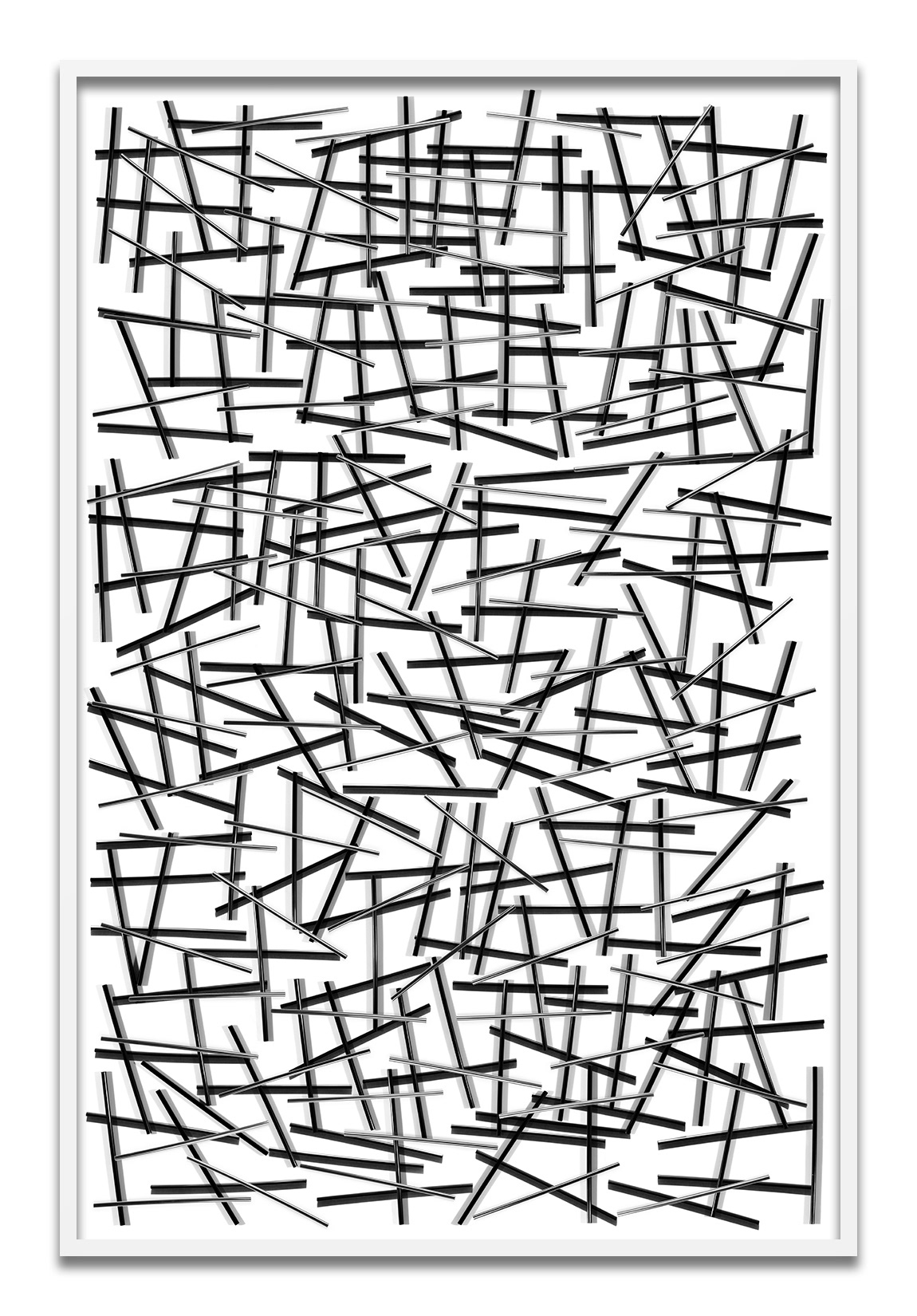

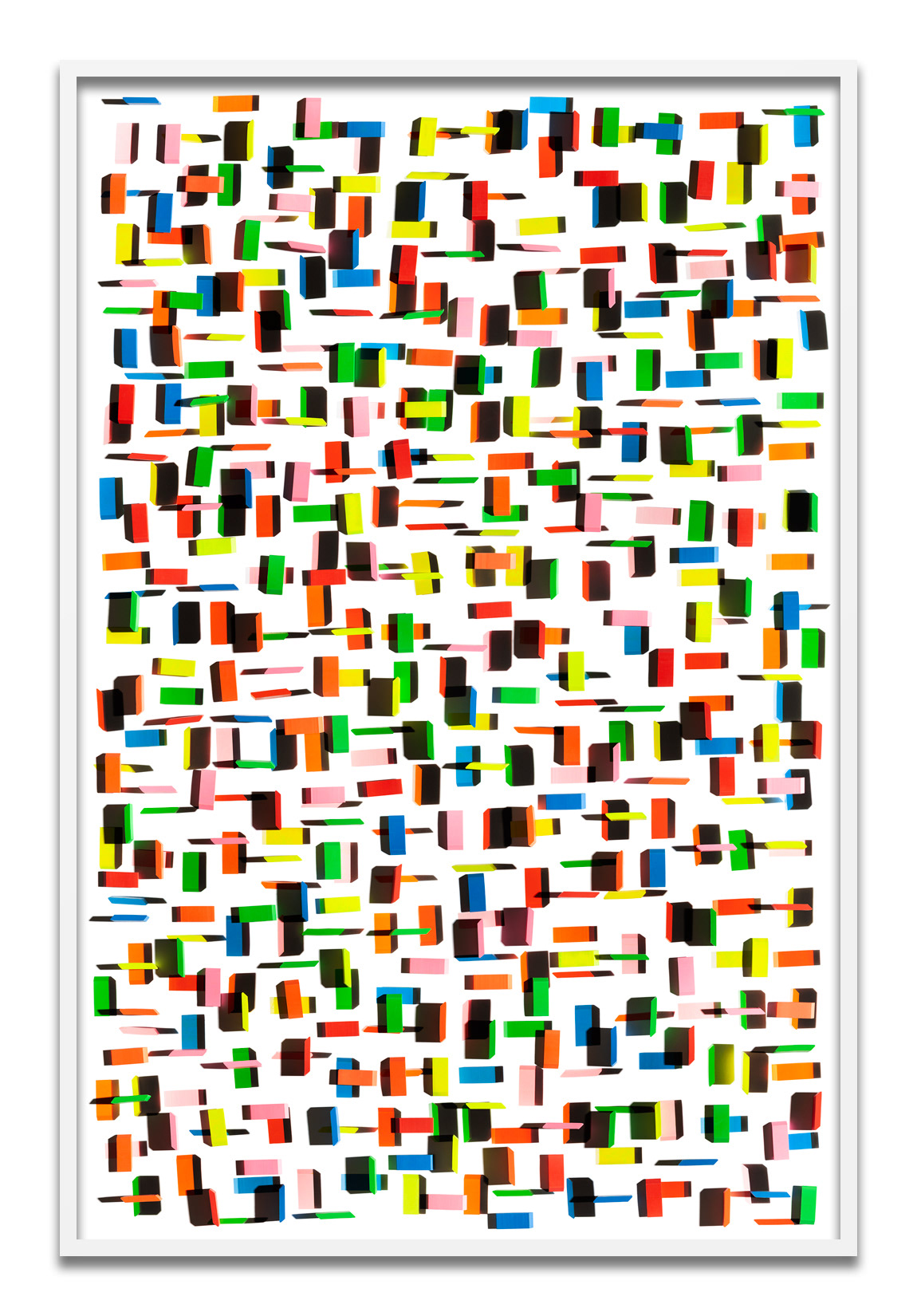

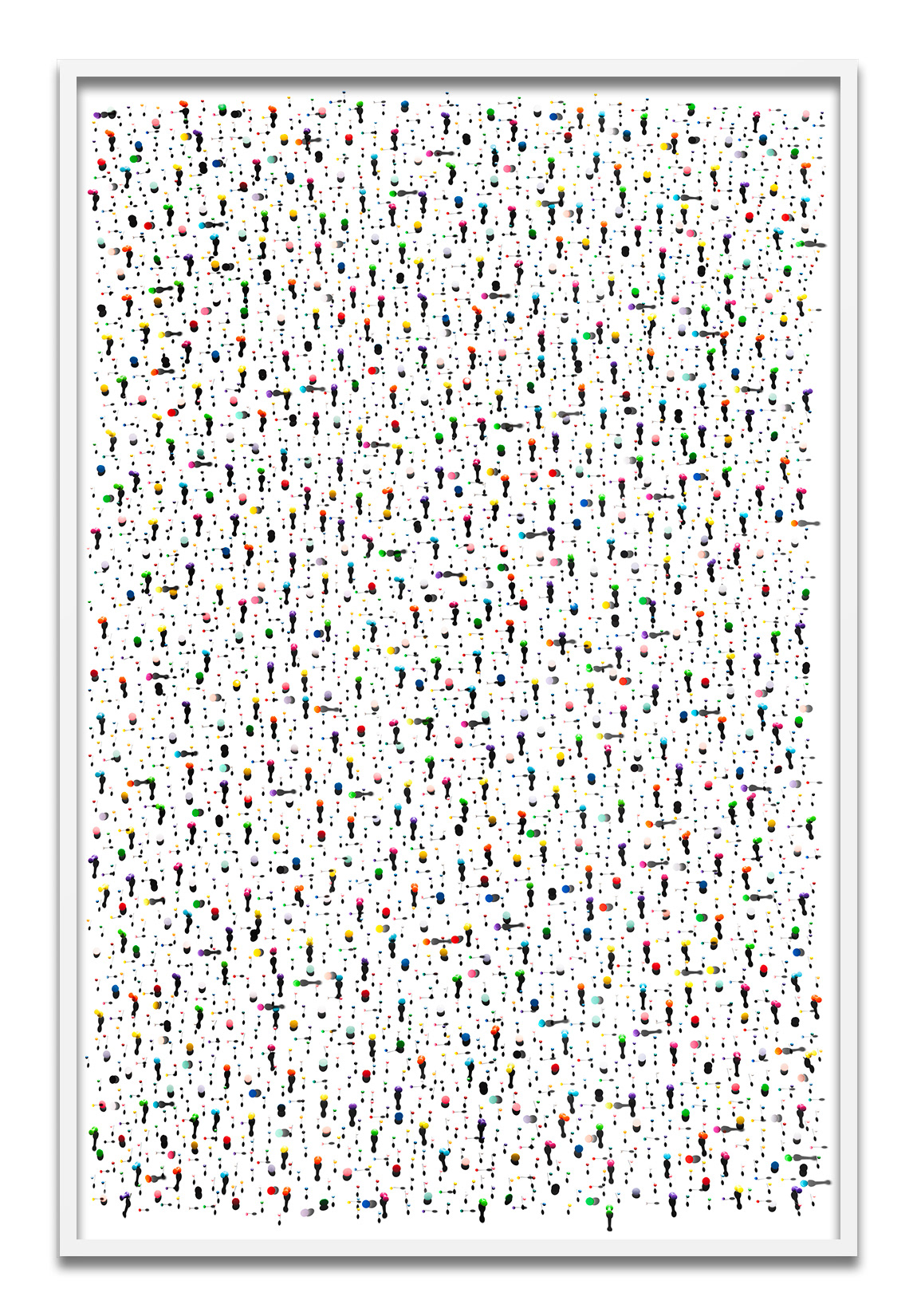

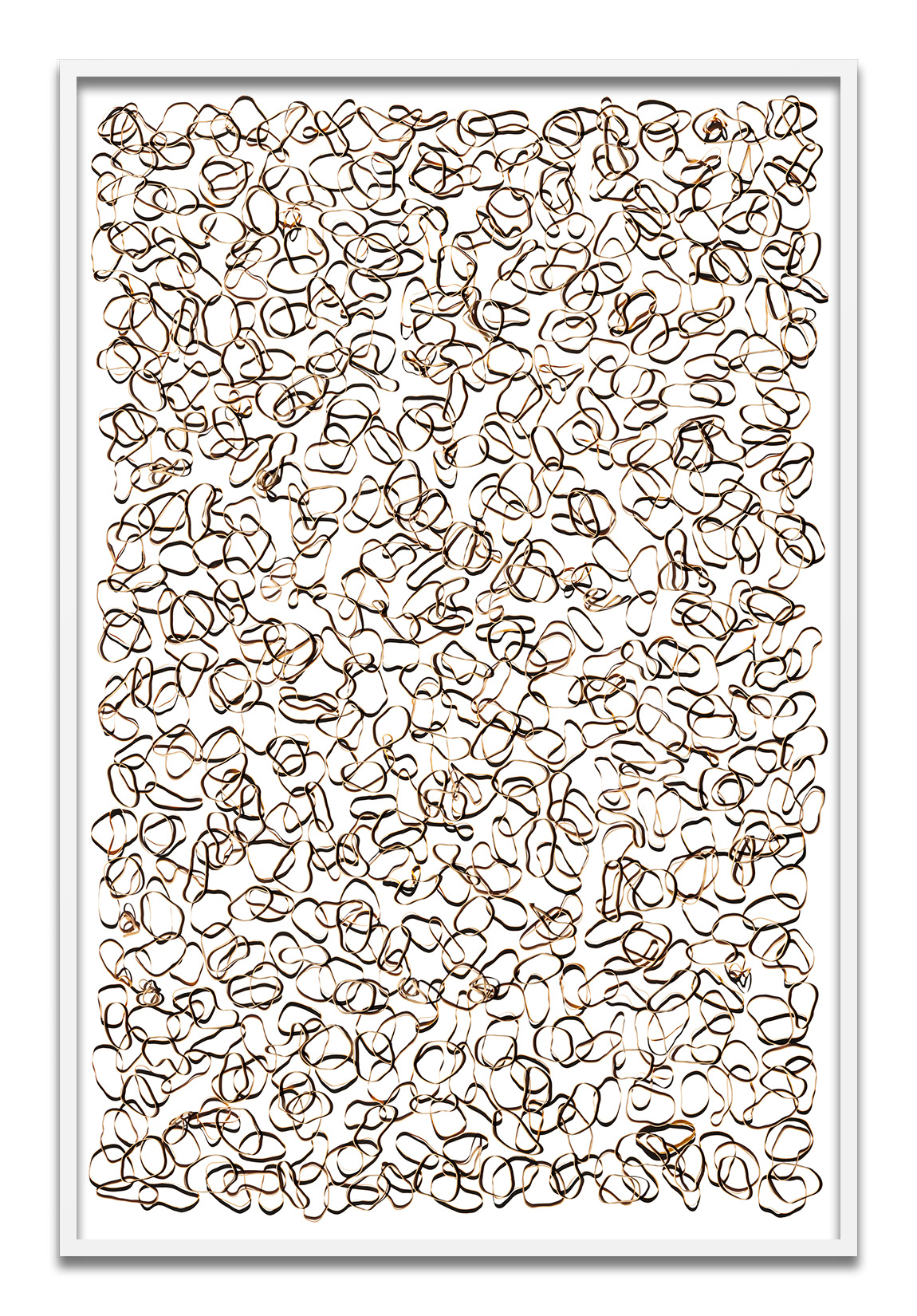

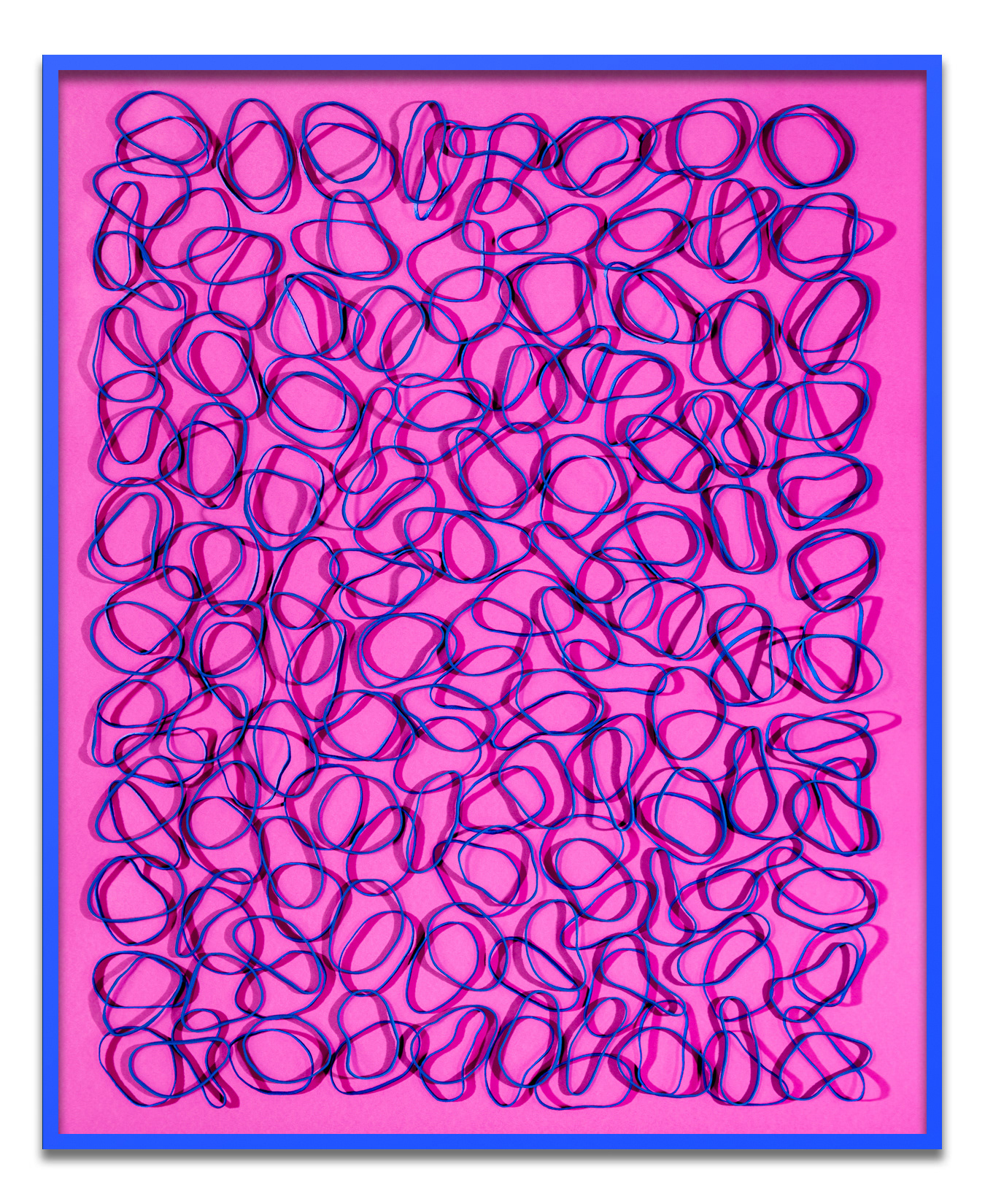

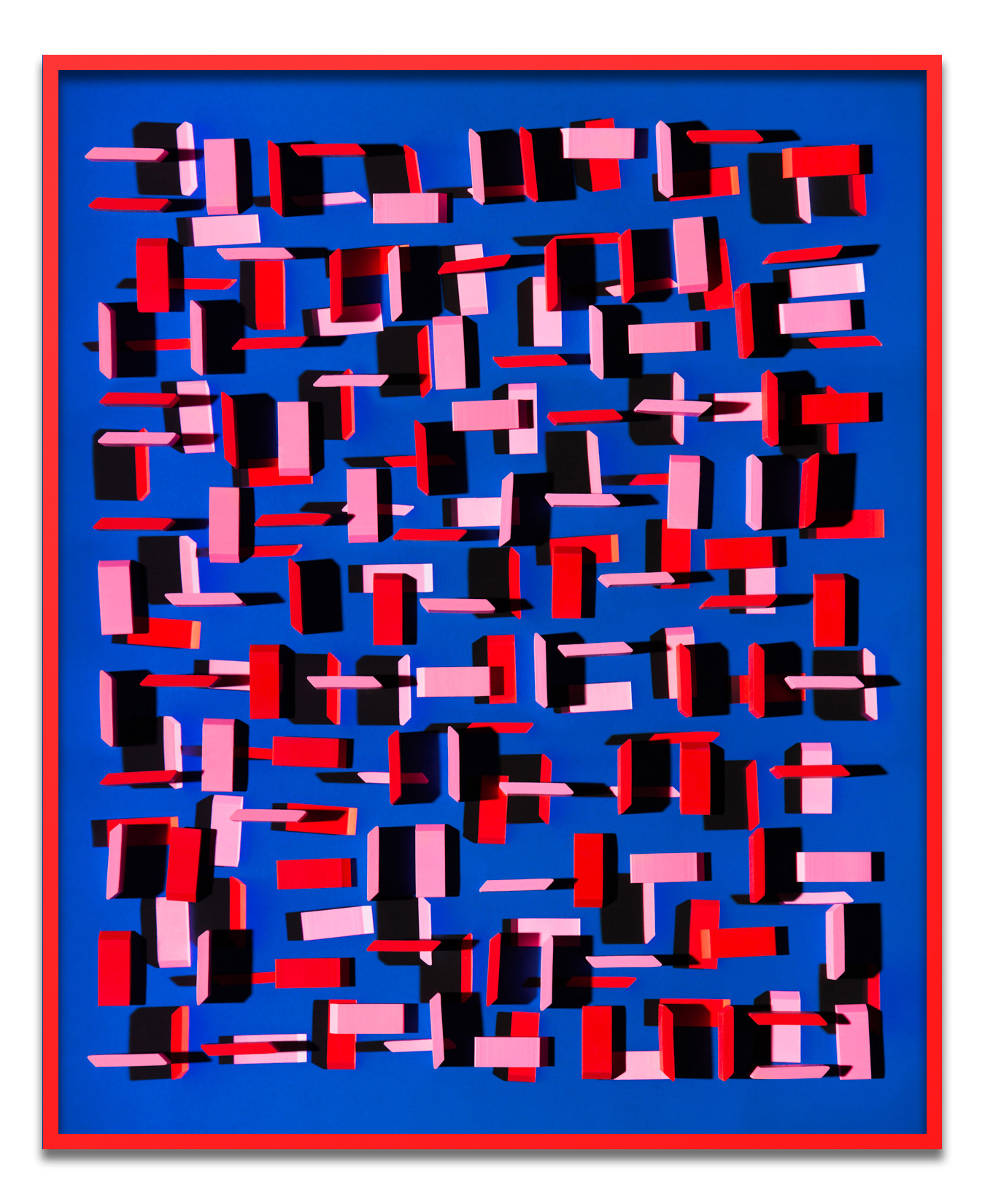

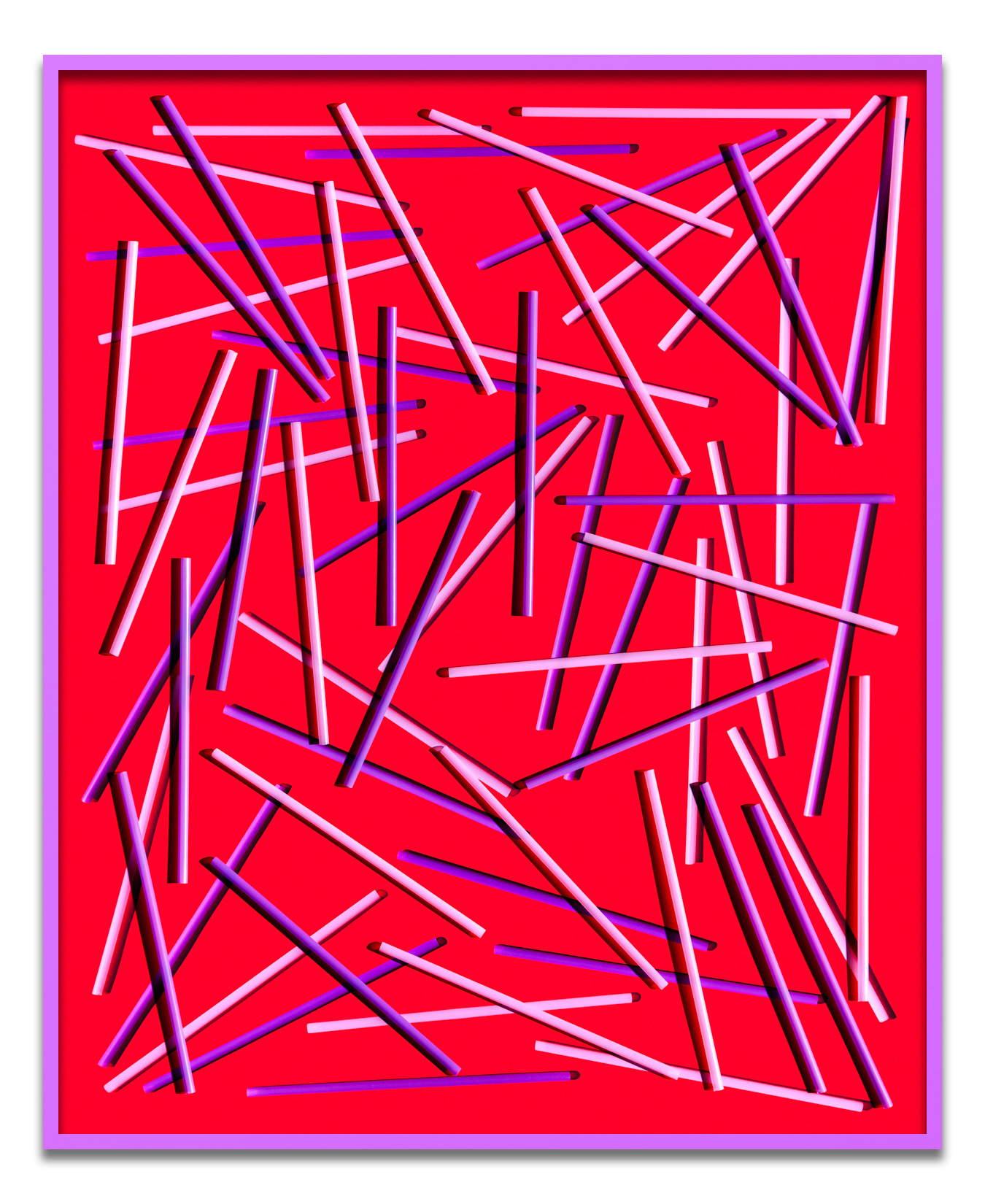

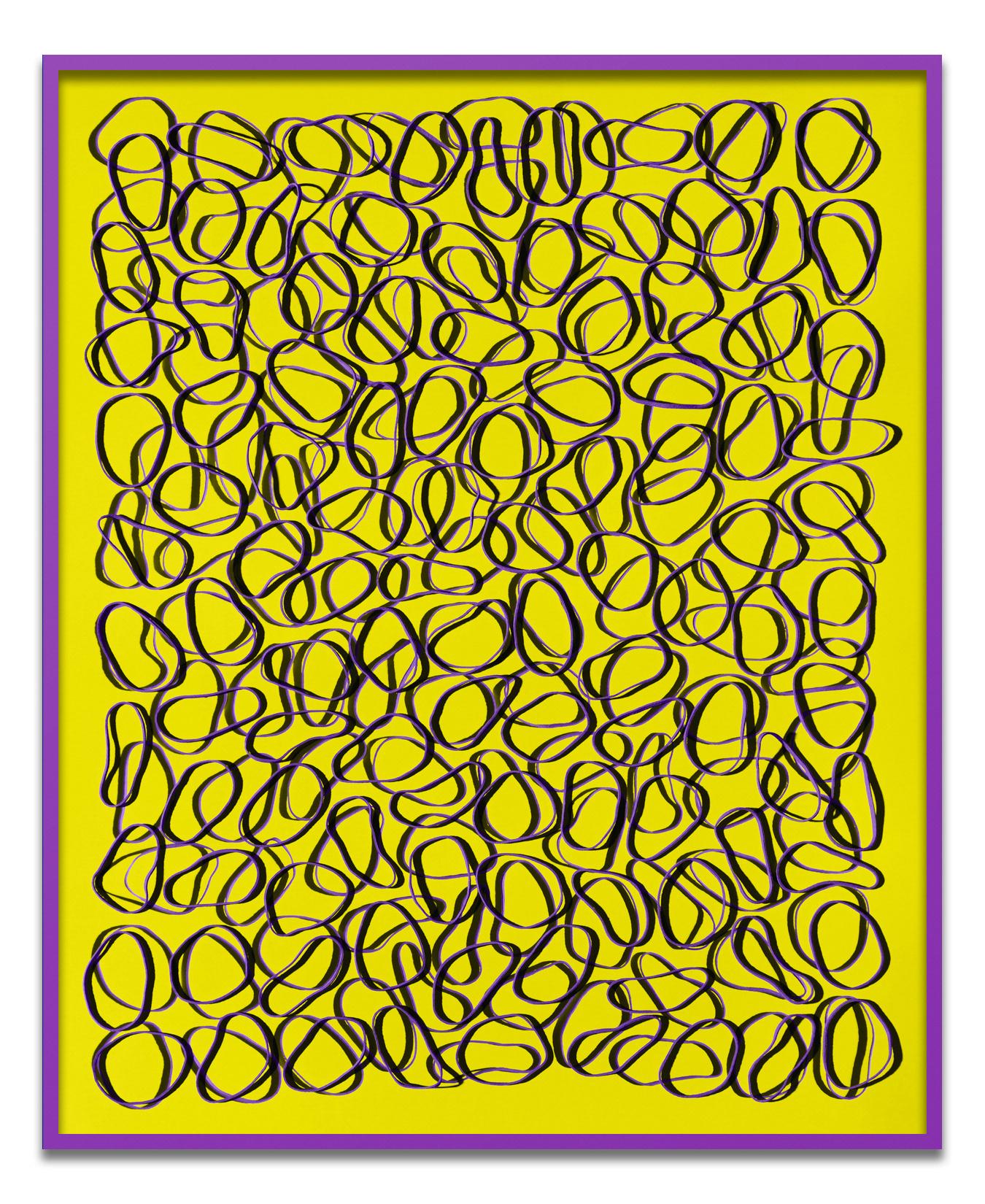

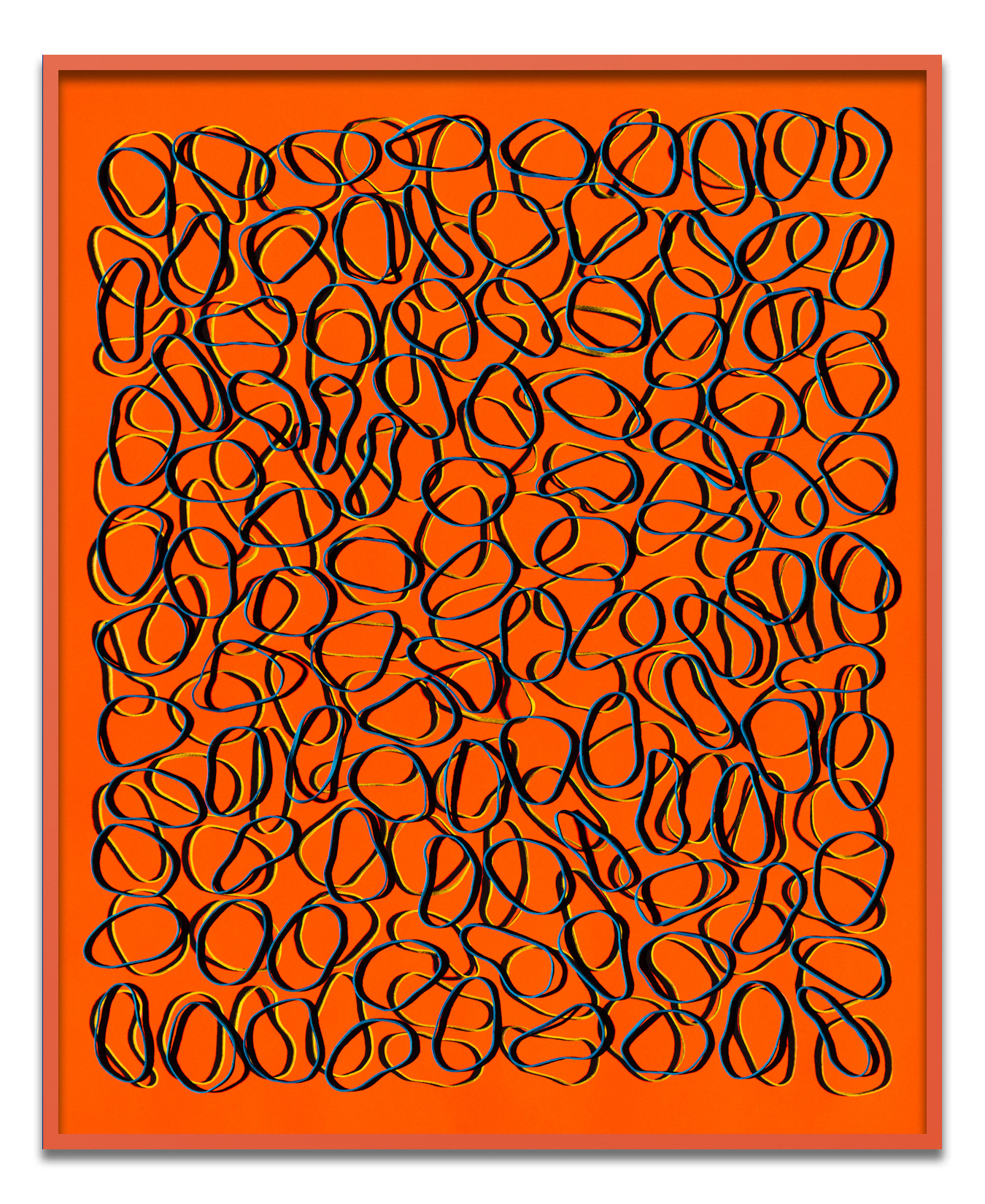

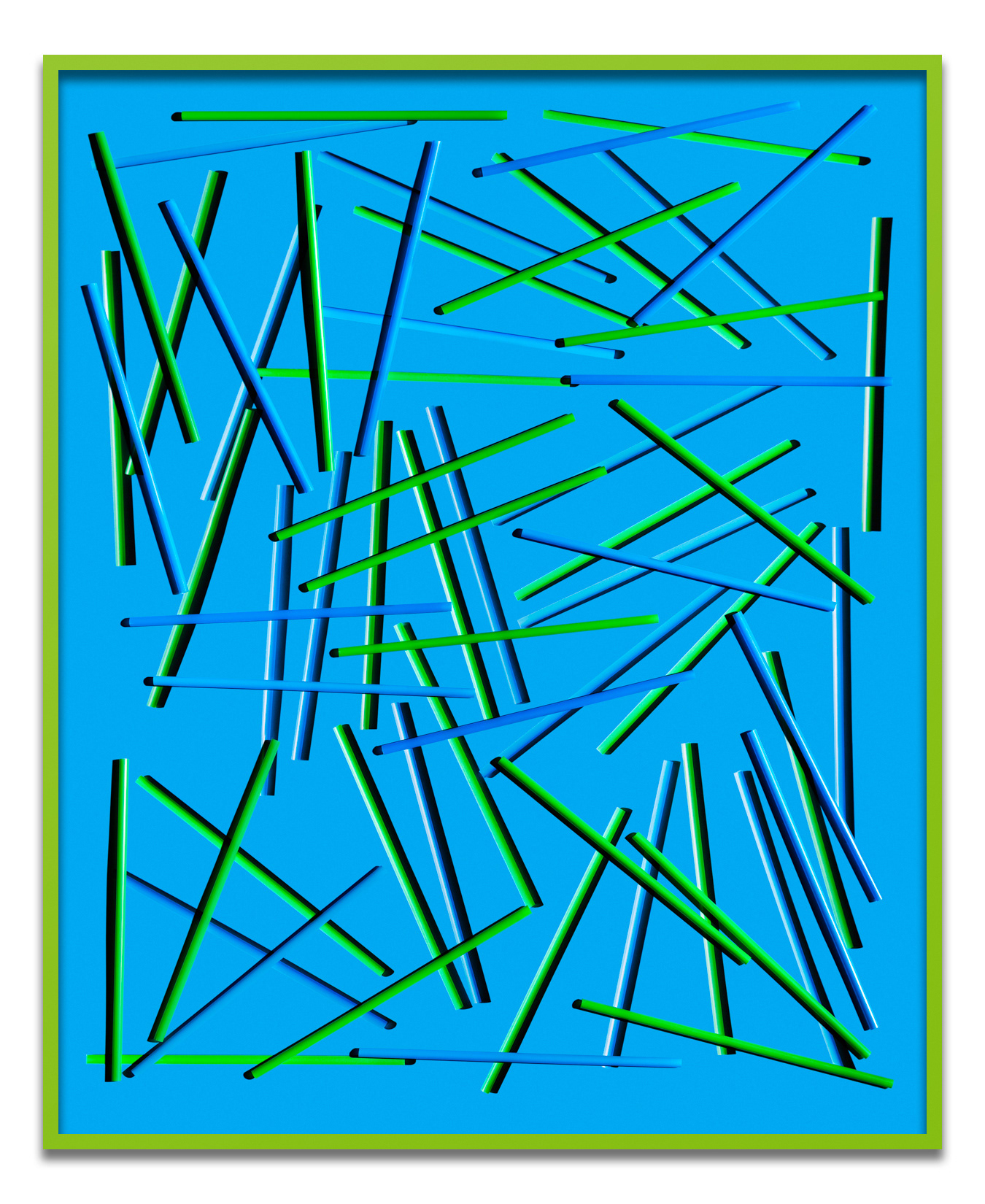

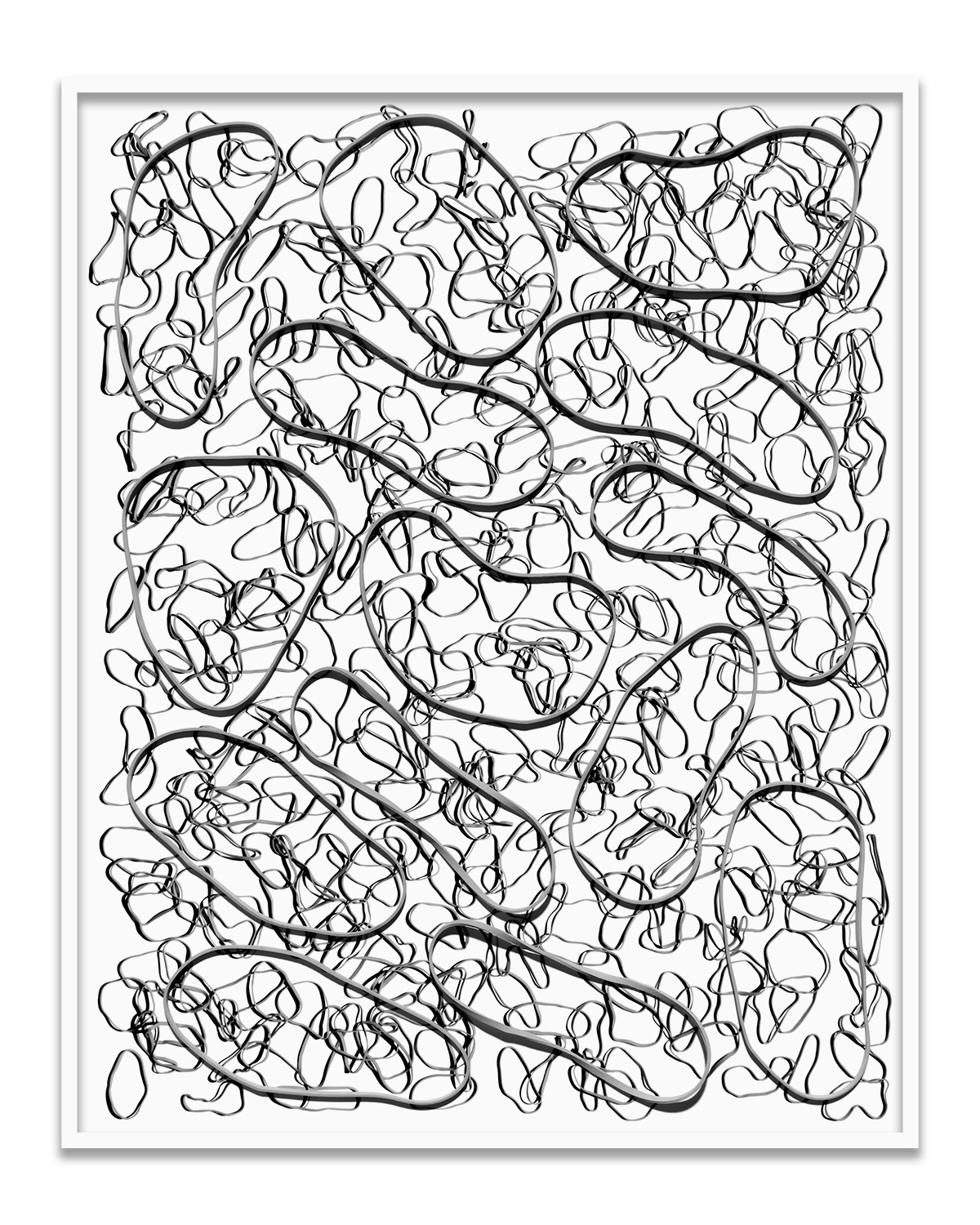

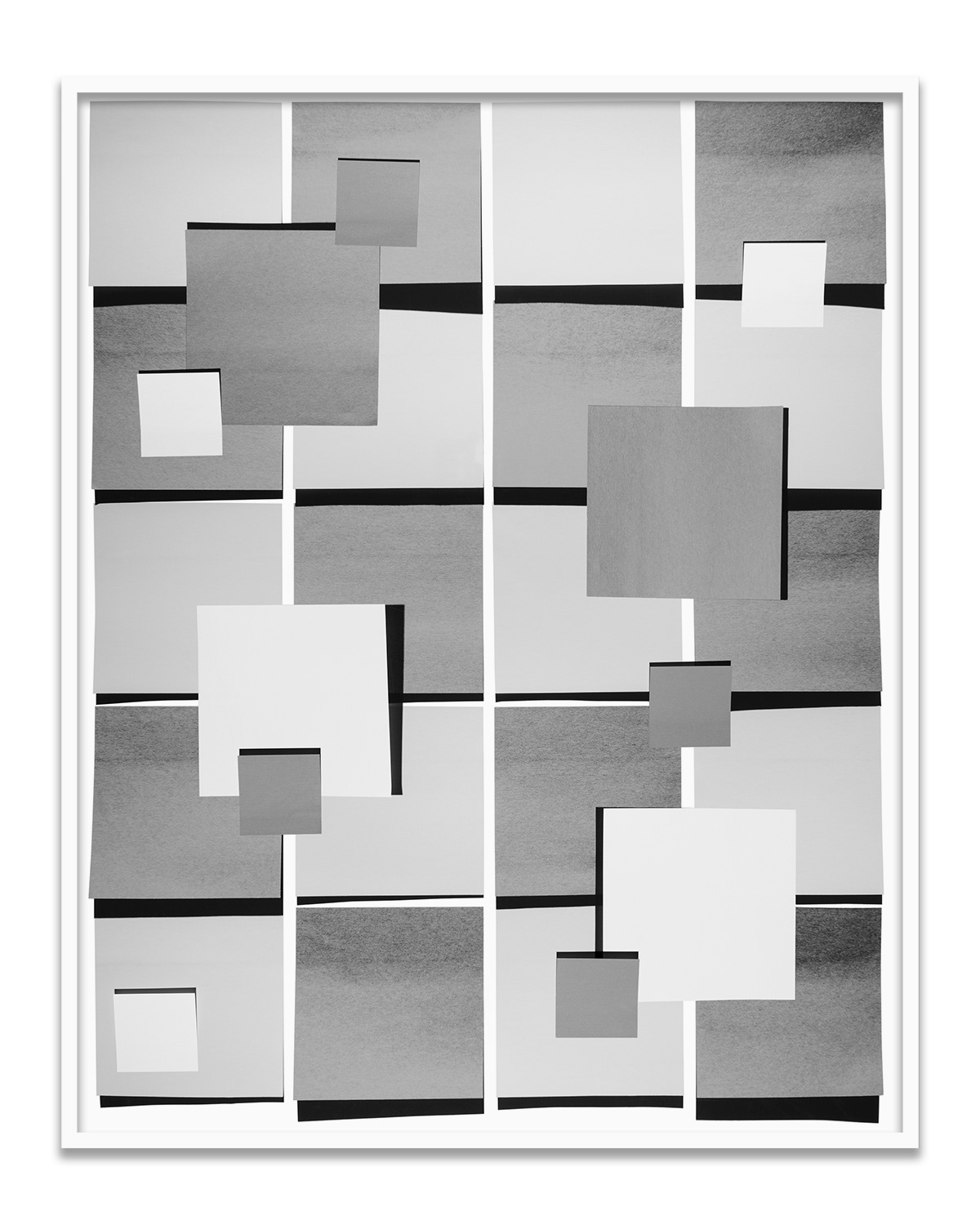

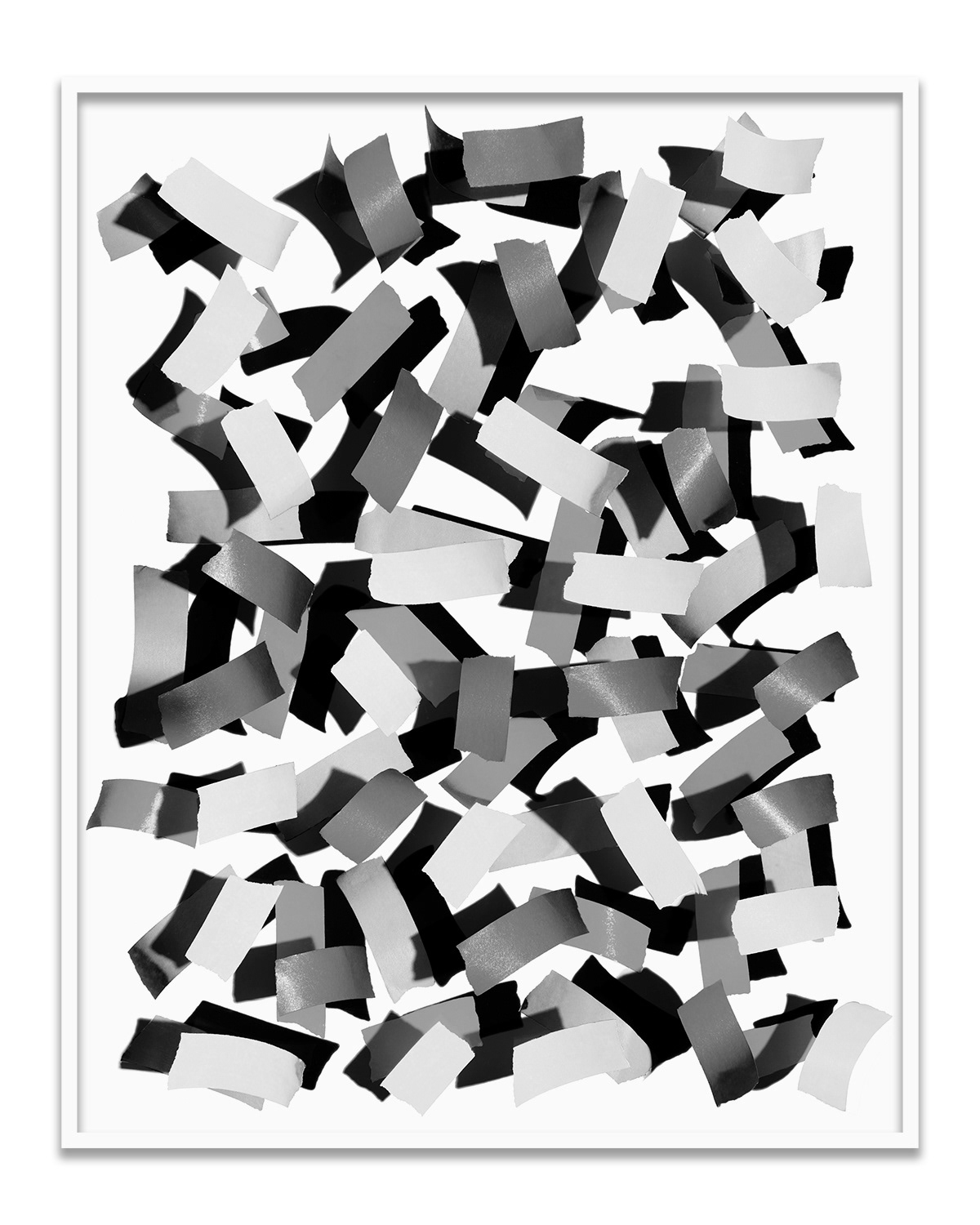

Using everyday objects I create compositions that are photographed, printed, relayered with more objects and photographed again. In some of the works I repeat the process a third time. For each layer I change the direction of the light, creating an image that does not make visual sense as a single photograph. One object casts a shadow to its right side while another to its left. In an otherwise evenly lit scene this could not naturally occur. Further, the top layer of objects seem to sit flat and on the same plane as the layers below, confusing real and photographic space.

In a photograph shadows are as solid and permanent as any object. In life shadows are fleeting, shift, and change, whereas in a photograph they are as immovable as the objects in the frame, captured at a point in time and locked into place. Shadows and objects alike become shapes and textures on a flat plane. In laying objects on top of the physical photograph and rephotographing the result, two types of space are captured in the resulting frame; the two-dimensional space of the printed photograph and the three-dimensional space that the objects exist within. This collapsing of space becomes visually hard to decipher. Because the photograph is a static scene from a fixed point of view, one cannot move their body in relation to it to see a different angle. Photography is most often used as a tool to make sense of what is in front of the camera, but I am interested in how it has the ability to complicate, compress and defamiliarize it.